History of Kingsland Manor

In 1941, architects from the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) documented “The Kingsland House”. Three other buildings in Nutley were already documented: the James R. Hay House on Passaic Avenue, the Rutandt House on Prospect Avenue, and the Vreeland Homestead on Chestnut Street. HABS was a federal government-funded program employing architects and historians during the Great Depression in a project to identify and document buildings of historic value and importance to communities across our nation. Although there were several additional owners of the Kingsland House, it was associated in 1941 with its most prominent owners, the Kingslands. Today, only the Vreeland Homestead and the Kingsland Manor remain.

The Building of Kingsland Manor

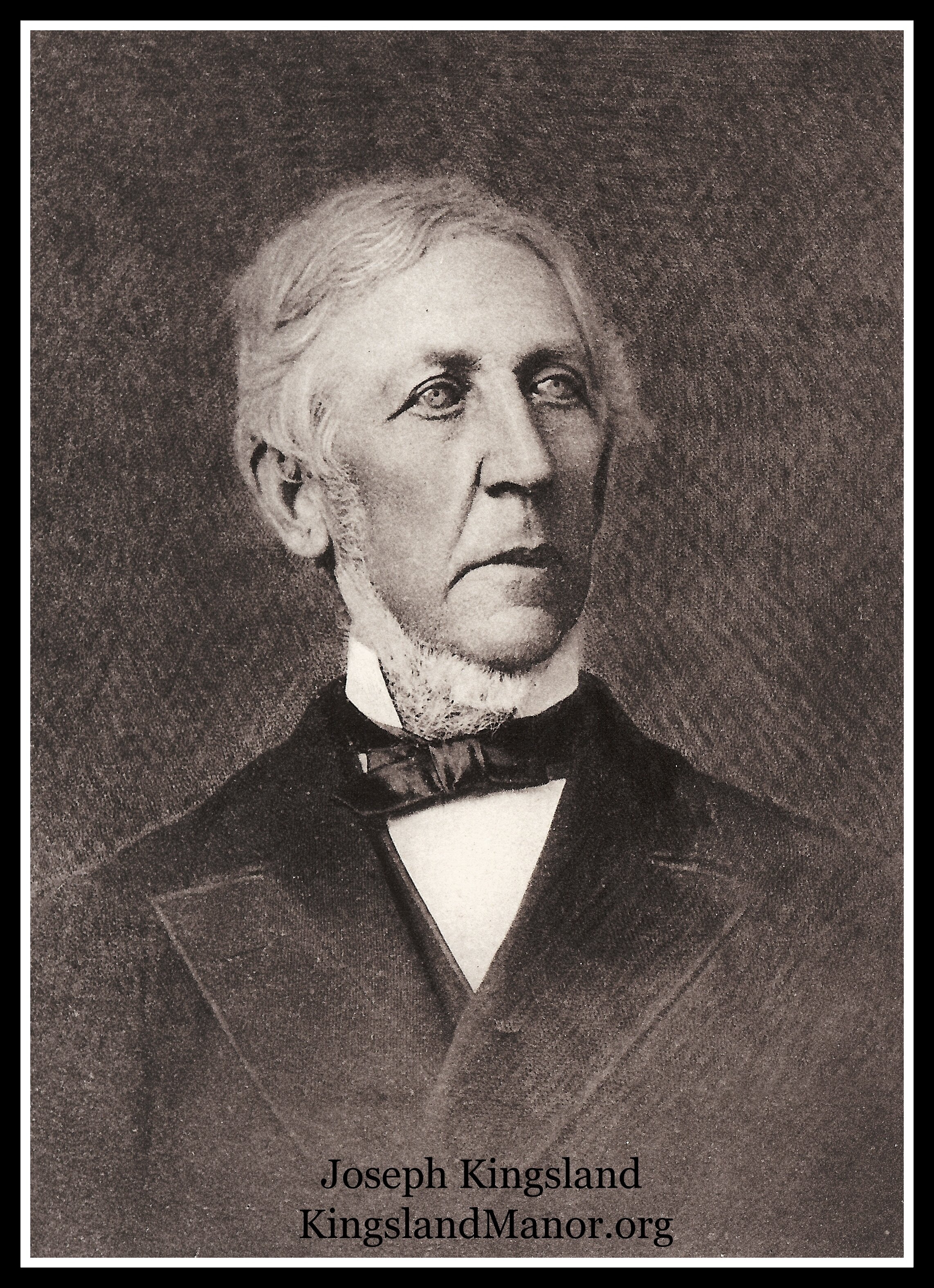

The Kingsland Manor was built in around 1768 by John Walls as a farmhouse for his son James and daughter-in-law Mary. John Walls ran lumber mill up the river that he acquired from a John Robinson in 1753. In 1787, Joseph Kingsland, a contractor living in New York City, was awarded a contract to install wooden curbing in the city. Joseph Kingsland was the grandson of Isaac Kingsland, who emigrated from Barbados to what is now Bergen County in 1668/1669. Isaac’s home in a portion of “New Barbadoes”—currently Lyndhurst—was across the Passaic River from where the lumber mill was located, and that was where Joseph was raised. When Joseph received the city contract, he needed an ample supply of hardwood and a mill to cut it. Remembering the Walls mill and the woodlands surrounding it, he came to North Belleville (Nutley) and offered to purchase the farmhouse and lumber mill. The property was sold to Joseph, but it took him another three years before he cleared all the liens on the property and took ownership in 1790. It took him another six years while he fulfilled his contract to the city to raise the ceilings and plaster the walls to make the home “livable” for his wife and children.

Tall Tales

The house has been described as containing “17 rooms, 2 kitchens, ballroom, slave prison, slaughter house, smoke house and underground Indian raid cellar, 125 foot tunnel leading to a stone barn fort, solitary confinement torture pen with manacle leg irons, neck yokes, a double ball and chain captors”. How much of this is lore?

There were probably no Indian raids in 1796. A sub-basement, most likely a root cellar, was probably the “underground Indian raid cellar.”

A resident of Clifton swears the tunnel still traverses her yard, and a number of Nutley residents claim they saw the chains and manacles. A Nutley man says he was present the day the tunnel was bricked up.

Evidence indicates that Joseph Kingsland was very considerate and humane in his dealings with his slaves. The tales of manacles and a torture pen do not agree with his last will and testament concerning the care of his slaves after his death. Legends of the Manor as a station on the underground railroad prior to the Civil War also tend to discredit any tales of mistreatment of Kingsland servants.

The Kingslands’ Contributions

Joseph’s son, Joseph Jr., partnered with his brother-in-law, Peter Morris, to take the sawdust waste from the lumber mill and turn it into paper. Joseph Sr. helped finance the establishment of the Kingsland paper enterprise. Adding to their fortunes, they branched out to grinding wheat and corn in a gristmill and selling ice. In 1821, Joseph Sr. died, leaving the Kingsland Manor and properties to his son Joseph Jr (aka Joseph II). Joseph III continued the family businesses until his death in 1899. Joseph III’s sisters sold the property in 1909. The Kingsland legacy extended through three generations and three centuries. That period included a partnering with George LaMonte, the producer of a “safety paper” that revolutionized the financial industry and was used by banks, stock investment firms, and the federal government.

A Colorful Chapter

In 1909, a Chicago politician and lawyer named Dan McGinnity purchased the Kingsland Manor to use the building and grounds as a training site for pugilists. Dan partnered with Bob Fitzsimmons, a professional boxer who was the sport’s first three-division world champion. “Diamond” Dan was married to Katherine Agnes, and they had a child, Bernard Charles. Bernard, nicknamed “Bus”, was educated in the Nutley School system and graduated from high school in 1919. In 1921, Bus became a constable in the third ward of Nutley. By 1927, he was a freelance cartoonist for the New York American newspaper. That year, Bus opened a speakeasy in the basement of the Kingsland Manor. He operated the speakeasy until Prohibition ended, and when the law was repealed, he opened the “Colonial Club” in the ballroom. Unfortunately, one December night in 1936, Bus served alcohol to a couple of non-members who were state alcohol and beverages commissioners, and he lost his club license. Under murky circumstances, his body was found outside of a barn across from the Manor with a gun lying next to him. He had been shot in the head. He was 37.

Katherine Agnes McGinnity ran the Kingsland Manor as the Nutley Private Hospital until 1938, when she lost the property due to unpaid taxes. In 1939, Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Smith acquired the Manor in a sheriff’s sale. Ralph was an air traffic controller at Newark Airport. It was during the period when the Smiths lived at the Manor that it was documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

The Saving of Kingsland Manor

In 1944, the Manor was purchased by International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) and became the home of one of its vice presidents, L. John Denny. Denny lived in the Manor until 1958, when the property was sold and inhabited by Norman and Doris Schepps. The Schepps sold many of the original furnishings from the colonial home in their antiques store in Chatham, Massachusetts during a period known as Colonial or Early American Revival.

In 1971, the Schepps sold the Manor to a developer, Albert Mardirossian, who wanted to subdivide the property and build four modern homes in its place. He approached the Nutley Planning Board with his proposal. However, planning board member Kenneth Sutphen was moved by the importance the federal government had placed on the Manor by documenting it under the HABS program. The planning board turned down the proposal and opted to purchase the property through Green Acre Funds. In 1974, the Historic Restoration Trust of Nutley Township was established as a partnership between the Friends of Kingsland Manor and the Parks and Recreation Commission of Nutley. For the past 46 years, the Trust has been faithful to the original design of the Manor, using HABS pictures, drawings, and descriptions as the basis for its restoration work.

In 1978, the Kingsland Manor was added to the National Register of Historic Places (#78001762) and the New Jersey Register of Historic Places (ID #1349).

In 2021, the Nutley Historic Preservation Committee added Kingsland Manor to its register of Historic Places in Nutley.

In May 2024, the Township of Nutley issued a proclamation recognizing the accomplishments of the Historic Restoration Trust of Nutley Township during its first 50 years. These accomplishments are summarized in a 50th Anniversary Brochure.